I recently read a brief summary of the Environmental Defence Society (EDS) report on land and water policy rollouts. It makes the statement that in the future there should be greater focus on implementation.

When applying a design lens to the implementation of anything new, it is critical we understand the various likely social implications, ie. who is the user or customer, and where are they and who influences them in their life journey.

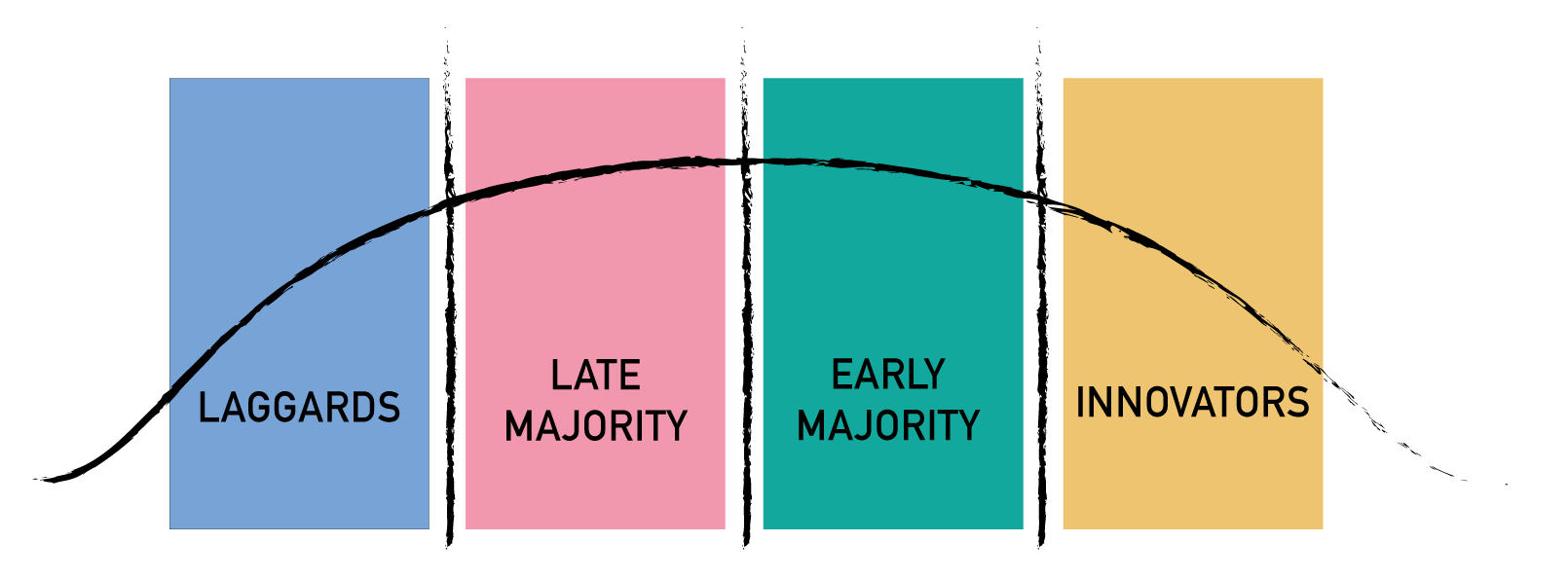

In terms of farming, a simple interpretation of the adoption curve would serve to show where the most effort to create change should be applied, what to be aware of, and the pitfalls of assumptions. In business, we often refer to an adoption curve when mapping a sales life-cycle of a product or system. In this case:

At one end of the adoption curve we have those farmers who are opposed to any change, and will lay the blame of change on the government of the day. In the model, these are known as the ‘laggards’.

We have those at the other end, who embrace change, know where their and the country’s future growth will come from, and are prepared to meet the challenges. The model calls those the ‘innovators’.

In the middle we have by far the largest cohort, often described as ‘early majority’ and ‘late majority’. Thus covering a great deal of variation between those farmers who are struggling to understand how they can change, and those who may understand the need, but are not sure where to start.

“For our efforts to be effective, those farming communities that make up the majority are those with whom we need to align our efforts. Both of these sectors need a design plan, which includes recognising the importance of an individual’s capacity for making change.“

At one end of the adoption curve we have those farmers who are opposed to any change, and will lay the blame of change on the government of the day. In the model, these are known as the ‘laggards’.

We have those at the other end, who embrace change, know where their and the country’s future growth will come from, and are prepared to meet the challenges. The model calls those the ‘innovators’.

In the middle we have by far the largest cohort, often described as ‘early majority’ and ‘late majority’. Thus covering a great deal of variation between those farmers who are struggling to understand how they can change, and those who may understand the need, but are not sure where to start.

For our efforts to be effective, those farming communities that make up the majority are those with whom we need to align our efforts. Both of these sectors need a design plan, which includes recognising the importance of an individual’s capacity for making change. While researching for this article, I came across an article in The Press, under the banner: ‘’When science and policy don’t align”. Like the summary, the article points out that in the future there should be a greater focus on implementation. When we talk about science and policy not aligning, it may well be that we have forgotten where the greatest impact will occur, and with whom – all part of including human interaction as part of a robust design process.

Governments rarely lead but respond to mega trends. The trends in this case are very clear; that we must satisfy the standards being set by international consumers, or see our markets die. The government is also reacting to a commitment to align our human activities with our cultural and environmental assets.

Back to those real people in the middle of the curve. Those farmers who love the land, and apply what they have learned over the years to taking care of it. How welcoming do we think they are of scientists telling them that everything they’re doing is wrong, and using policy change as a hammer? We need to recognise the effect of urban populations blaming farmers for the state of our ecologies. They are easy targets. It is no surprise then, that farmers are apt to regard policy makers as ignorant ‘city slickers’, eager to make scapegoats of their communities, and scientists as highly educated and highly funded ‘know-it-alls’.

There is such a thing as being overwhelmed. Many of us are feeling it. No less those on the land, who are being hammered with information from experts, so much so that they are unable to prioritise action.

“We need to recognise the effect of urban populations blaming farmers for the state of our ecologies. They are easy targets. It is no surprise then, that farmers are apt to regard policy makers as ignorant ‘city slickers’, eager to make scapegoats of their communities, and scientists as highly educated and highly funded ‘know-it-alls’. “

Back to those real people in the middle of the curve. Those farmers who love the land, and apply what they have learned over the years to taking care of it. How welcoming do we think they are of scientists telling them that everything they’re doing is wrong, and using policy change as a hammer? We need to recognise the effect of urban populations blaming farmers for the state of our ecologies. They are easy targets. It is no surprise then, that farmers are apt to regard policy makers as ignorant ‘city slickers’, eager to make scapegoats of their communities, and scientists as highly educated and highly funded ‘know-it-alls’.

There is such a thing as being overwhelmed. Many of us are feeling it. No less those on the land, who are being hammered with information from experts, so much so that they are unable to prioritise action.

Overwhelm is dangerous, and could’ve been predicted by both the scientists and the policy makers. It reminds me of a time when a university developed, at great expense, technologies for wooden commercial buildings in New Zealand. This was at a time post-earthquake when traditional structures were in question. The university was proud of its achievements, and published them widely. But adoption was tragically slow.

A simple answer may have been that the university failed to understand the world of developers, architects and builders, and in doing so, failed to produce adoption tools. Simply put, the ‘how-to’.

In the case of our farmers, it might have been how to prioritise. In my language, how to address overwhelm- a simple but compelling idea that may help to change one of our most pressing challenges.